How To: Create Digital ID for Inclusive Development. Thank the CIA’s USAID

What they started in Africa is coming to you, very soon. No benefits, only major data risks. And the ID is only the start of what will be sent to the cloud.

https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/2022-12/Digital_Identity_HowTo_Guide_1.pdf

page 17

PART I: HOW ID SUPPORTS PROJECT BENEFICIARIES

Once the implementer for this activity is selected, they begin by

Engaging Multiple Partners in the Design Phase, conducting the

ID system mapping through a Design Workshop in which many of the

relevant partners participate. The ID component of their project is

tricky: they need to gather a lot of data on each program participant

for their own reporting; they need to find a way to lower the burden

on Joy in terms of getting a new ID; and they need to maintain a

positive relationship with the government while still respecting the

concerns of minorities like Joy. In the Design Workshop, they find out

that IDs have been used in the past as a way to identify and persecute

ethnic minorities. They also learn that several of Joy’s fellow farmers

have trouble with fingerprint scanners due to labor-worn fingers.

They choose to remove the “ethnicity” field from their data collection

process and to offer both fingerprint registration and build in a fall-back

identity verification process via photo, for those who are excluded

from biometric registration due to their worn-down fingerprints.

During the Design Workshop, the implementer finds out that another

large NGO in the country has already registered nearly all vulnerable

people in the country. The new activity can use this same registration

process. However, since the new activity will gather information on

health and nutrition that may be considered sensitive, they will store

the data on their own protected servers. They also decide only

to share anonymized data with the government. This provides the

government with some value from the system, helping to maintain a

positive relationship, but it does not provide any personally identifiable

information given local concerns about potential misuse of information

by the government. When Joy learns this, she is relieved, as she has

more confidence that the government will not receive additional

information on her besides what is required for the social protection

plan. This level of confidence is the result of the implementer taking

the time to Ensure Trust through Data Protection and taking a

nuanced approach to Designing for Reuse and Interoperability.

Note: the data are stored as well as digitized for the citizen’s use. They contain sensitive health and nutrition information that could be used against the citizen. Governments are likely to obtain access to all the data. Biometric identification is a fail-safe requirement that will allow no one to opt out, once it is set up.—Nass

page 44

Choosing the right tech vendor is a critical piece of any digital ID implementation. In the context of USAID-funded activities, a project that needs to identify beneficiaries may choose to procure a beneficiary management system (BMS) that both identifies and collects additional data on participants for M&E (monitoring and evaluation) purposes.

New document:

From the executive Summary, page 5:

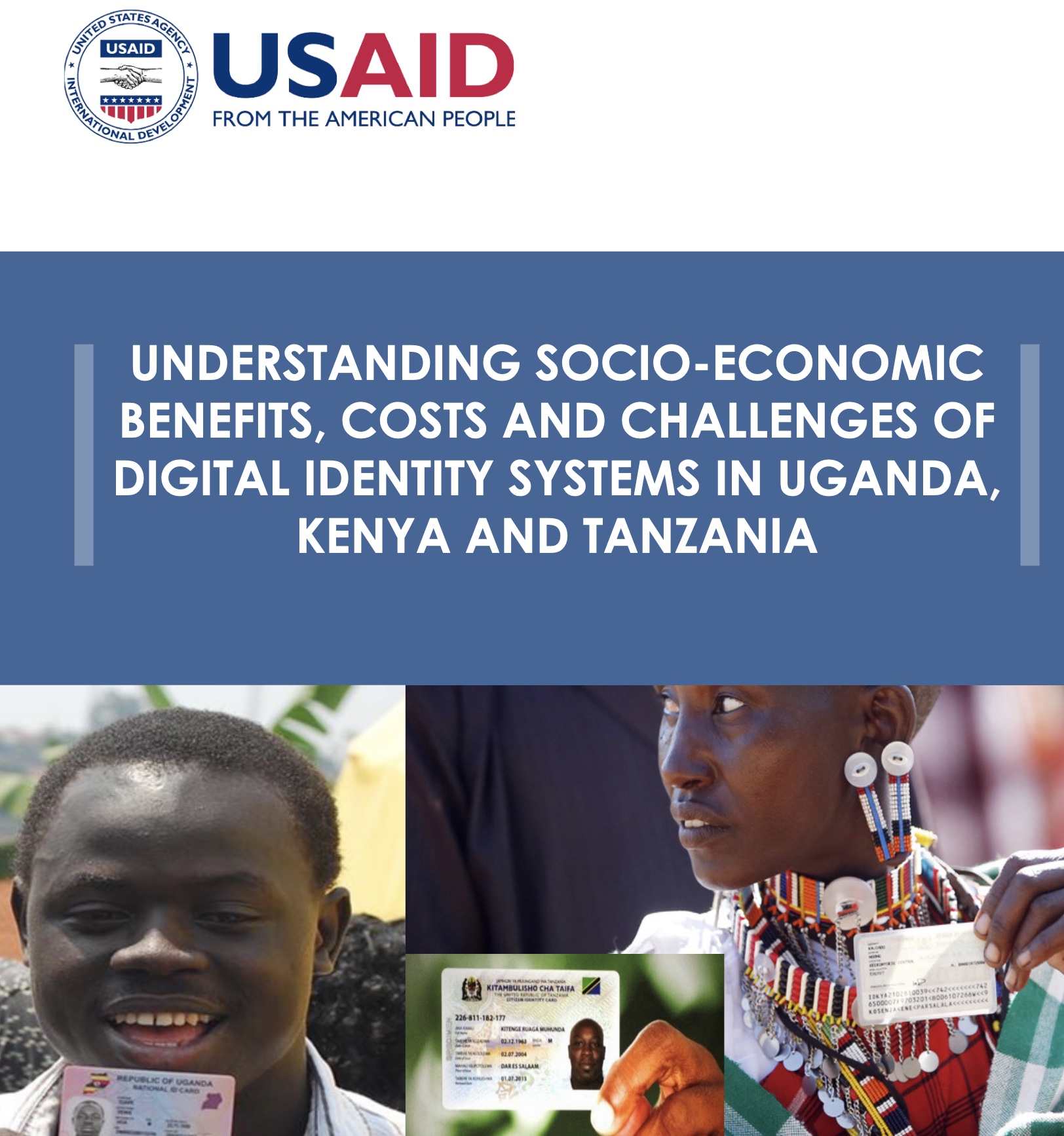

Over the last decade, countries in sub-Saharan Africa including East Africa have set up

and implemented electronic identification systems albeit at different stages. While the

primary purpose is fostering identification and accounting for individuals, they have been

used by governments for various civic and social services to the populace (Anderson, C. L.,

Biscaye, P. E. & Reynolds, T.W., 2013). The broadest of these systems – the national identities

(IDs) have involved registration of all adults together with capturing their biometric data.

However, USAID’s Center for Digital Development (CDD) notes that formative studies done

across sectors and countries report many development gains from digital identity systems,

but also common gaps depicting a fragmented ID landscape, siloed systems and short-

term design motivations. CDD also discovered a lack of strong evidence for exactly when and how identification systems provide value, both to institutions that invest in them, and individuals who use them (USAID, 2017).

And furthermore, page 6 reveals that risks are considerable, while as noted above, the benefits are illusory.