Report to Federal Officials on Sewage Sludge, PFAS and the horrendous consequences of land application to our food and water/ Laura Orlando and Meryl Nass

HIDDEN CRISIS: Highly toxic sewage sludge (mislabeled as healthy fertilizer) has been applied to 20% of US farmlands and gardens, massively contaminating US food, soil and groundwater.

April 2025

Overview Sewage treatment plants in the U.S. produce over 14 million tons of toxic sewage sludge annually. Instead of dumping sewage far offshore, the EPA signed a consent agreement in the 1980s to encourage the processing of sewage and its application to agricultural land as fertilizer. Ignored by this plan was the unpredictable variety and amount of chemicals and industrial wastes contained in the mix, and the fact that “processing” was rudimentary and failed to remove any toxins. The EPA still does not know what is contained in sludge, does not require measurement of toxic materials (except several elements) and has never sought to investigate the individual or synergistic effects of these substances on human and animal health.

In an August 2024 New York Times article, “Something’s Poisoning America’s Land,” we learned that “farmers have obtained permits to use sewage sludge on nearly 70 million acres, or about a fifth of all U.S. agricultural land.” The Times has published 9 articles on the sludge problem over the past 8 months, linked below.

Despite being marketed as a safe fertilizer and rebranded “biosolids,” sludge always contains PFAS, microplastics, pharmaceutical drug products and brominated flame retardants. When “applied” as a fertilizer, sludge poisons the land, the run-off enters waterways and its components contaminate the food supply.

PFAS substances persist in the environment indefinitely. Exposure has been linked with kidney cancer, liver disease, thyroid disorders, autoimmune disorders of the digestive system, and immune system impacts in children.

Key Concerns

-

Widespread PFAS Contamination: Depending on the chain length and other factors, some PFAS are taken up by crops and livestock while others migrate into groundwater and surface water, contaminating food and water supplies.

-

PFAS Exposure: PFOS, PFOA, and several other PFAS compounds are consistently found in high concentrations in sludge. These chemicals bioaccumulate, cause cancer, and affect immune, endocrine, and reproductive systems.

-

Microplastic Pollution: Over 90% of microplastics entering wastewater systems end up in sludge and contaminate the land where sludge is spread, disrupting soil health and inhibiting plant growth.

-

Unknown Substances: The unmonitored industrial release of chemical waste products into sewer systems leads to unpredictable, unknown and unmeasured hazards whose risks are borne by the public.

-

Poisoned Well Water: Rural communities are especially dependent on the safety of drinking water wells. Maine, the only state to systematically assess sludge spread on farms, found that roughly one in five households adjacent to the impacted farms had unsafe PFAS levels in their water.

-

Proven Risk from Contaminated Food: In January 2025, the EPA published a draft risk assessment indicating that the PFAS in a single application of sewage sludge can lead to an unacceptable increase in the risk of cancers and non-cancer health impacts for farming families.

Farmers and Ranchers Face Catastrophic Losses

PFAS-impacted farms have gone out of business in Texas, New Mexico, Colorado, Michigan, and Maine. For example:

-

Maine: Adam Nordell and Johanna Davis lost their organic farm in Unity, Maine after discovering severe PFAS contamination from sludge that had been “applied” on their land by previous owners. The contamination destroyed their crops, contaminated water sources, and resulted in high PFAS levels in their blood, forcing them to cease operations.

-

Texas: Dead livestock, crop damage, and health problems have been recorded in Johnson County, Texas on ranches near land that was spread with PFAS-contaminated sewage sludge (Texas Public Policy Foundation, 2024). Texas State Representative DeWayne Burns, who represents Johnson County, declared the county a disaster area due to sludge spreading. Texas State Rep. Helen Kerwin has proposed legislation to limit land application in the state.

Across the U.S., farmers and ranchers are facing devastating economic, health, and emotional consequences due to historical and ongoing sludge application. In 2021, the most recent year for which figures are available, 88% of all payouts made through the federal Dairy Indemnity Payment Program (DIPP) were to dairy farmers whose milk was contaminated by PFAS, underscoring the severity of the crisis and the national scale of its impact on the food supply.

State Actions to End Sludge Spreading

· The legislatures of Texas, Oklahoma, and Missouri are all considering Republican-sponsored bills to regulate PFAS levels in land-applied sludge or ban the practice entirely. Similar bills are moving forward in blue states.

· Maine and Connecticut have banned sludge application on land.

Policy Recommendation: Ban Land Application Nationwide

The land application of sewage sludge is regulated by federal law under Chapter 40 Part 503 of the Code of Federal Regulations (40 CFR 503, also called the Part 503 Sludge Rule). The EPA is required to:

-

“Establish numerical limits and management practices that protect public health and the environment from the reasonably anticipated adverse effects of toxic pollutants in sewage sludge.

-

Periodically review existing regulations for the purpose of identifying additional toxic pollutants that may be present in sewage sludge and assesses whether those pollutants may adversely affect public health or the environment based on their toxicity, persistence, concentration, mobility, and potential for exposure.”

-

Instead the EPA has performed modeling of limited risks, failed to consider the range of toxins present, and failed to evaluate their additive or synergistic impact on health

SOLUTIONS

1. Sufficient amounts of numerous toxic pollutants exist in sludge to warrant a blanket prohibition by the EPA against the use of sludge (a.k.a. biosolids) “applied” to land.

2. The FDA could alternatively issue a rule banning the future sale of meat and dairy from animals grown on sludge-treated land and could include other foods grown on land where sludge has been applied, or fertilizers produced from sludge have been used.

3. The long-term solution is to separate industrial and chemical wastes from human wastes, which could potentially be processed for fertilizer. Factories should be responsible for their own waste processing and disposal.

4. In the meantime, sewage sludge must be disposed of in lined pits or another manner that avoids contamination of groundwater, food products and soil.

Contact: Laura Orlando, Just Zero, Lorlando@just-zero.org; Abby Rockefeller; Meryl Nass, M.D.

Attachments:

1. Excerpts from the EPA Draft Risk Assessment, January 2025

2. Sierra Club testing of commercial bagged fertilizers found toxic PFAS levels in all but one

3. Links to articles about toxic sewage sludge by Hiroko Tabuchi in the New York Times, August 2024 – March 2025

______________________________

1. United States Office of Water EPA-820P25001

Environmental Protection 4304T January 2025

Agency

DRAFT SEWAGE SLUDGE RISK

ASSESSMENT FOR

PERFLUOROOCTANOIC ACID

(PFOA) CASRN 335-67-1 AND

PERFLUOROOCTANE SULFONIC

ACID (PFOS) CASRN 1763-23-1

January 2025

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Water, Office of

Science and Technology, Health and Ecological Criteria Division

Washington, D.C.

https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2025-01/draft-sewage-sludge-risk-assessment-pfoa-pfos.pdf

The material below is excerpted from the Executive Summary:

Modeling for land application scenarios suggests that, when the majority of the consumer’s dietary intake of a product comes from a property impacted by the land application of sewage sludge, the highest risk pathways include (1) drinking milk from majority pasture-raised cows consuming contaminated forage, soil, and water, (2) drinking water sourced from contaminated surface or groundwater on or adjacent to the impacted property, (3) eating fish from a lake impacted by runoff from the impacted property, and (4) eating beef or eggs from majority pasture-raised hens or cattle where the pasture has received impacted sewage sludge. The risk calculations assume each of these farm products (e.g., milk, beef, eggs) or drinking water consumed comes from the impacted property but does not combine risks from each of these products. The EPA did not estimate risk associated with occasionally consuming products impacted by land application of contaminated sewage sludge nor foods that come from a variety of sources (e.g., milk from a grocery store that is sourced from many farms and mixed together before being bottled)….

In summary, the results of the draft risk assessment indicate that there are potential risks to human health to those living on or near impacted properties or primarily relying on their products from land application and surface disposal of sewage sludge containing PFOA and PFOS and that risk is dependent on (1) the concentration of PFOA and PFOS in sewage sludge, (2) the specific type of management practice (e.g., type of land application or presence of a liner in a monofill), and (3) the local environmental and geological conditions (e.g., climate and distance to groundwater).

Risks are possible, though not quantified, from the incineration of PFOA and PFOS-containing sewage sludge. Site-specific factors should be considered when planning risk mitigation and management practices to reduce human exposures associated with PFOA and PFOS in sewage sludge.

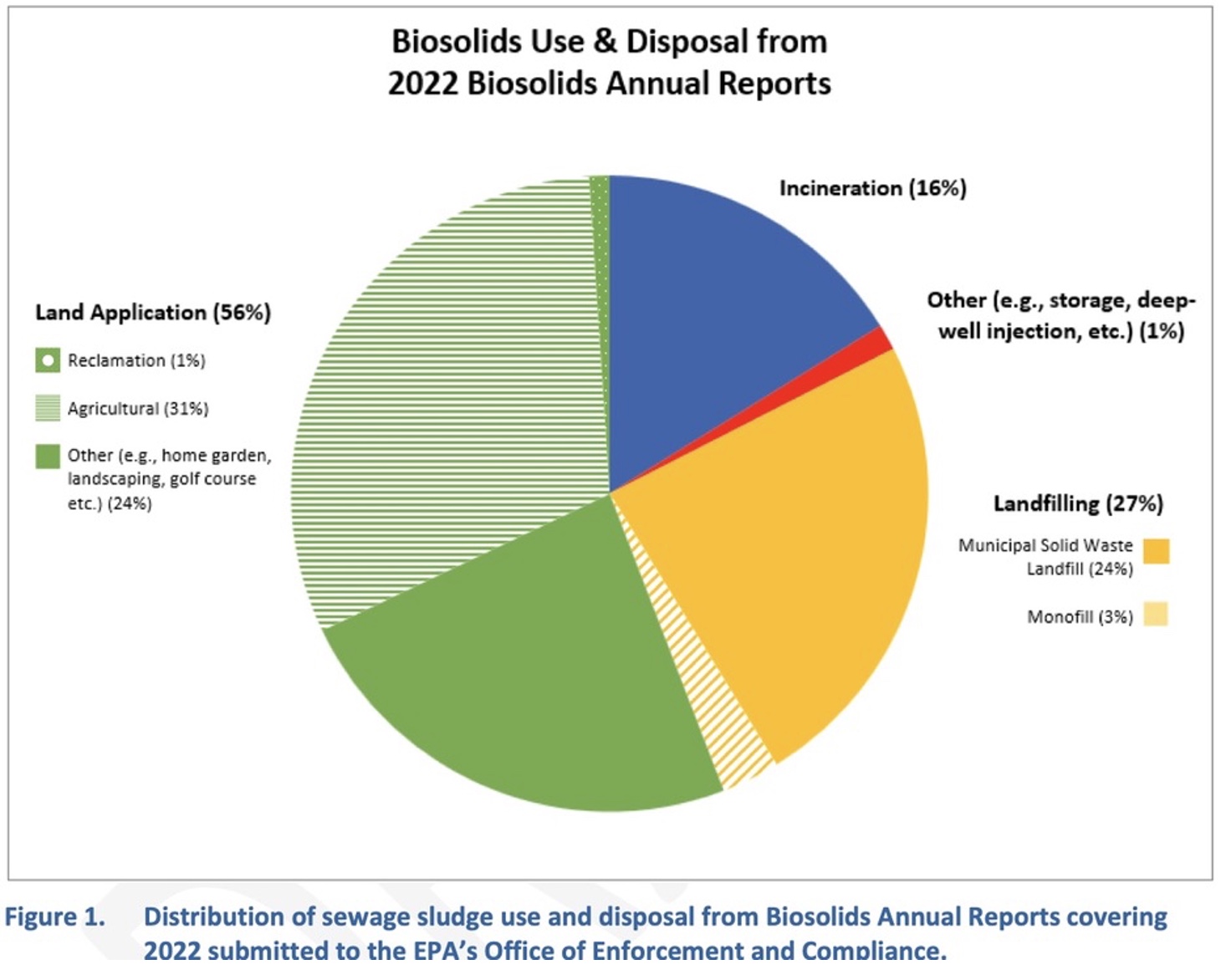

31% of sewage sludge is spread on agricultural land and 24% is used for home gardens and landscaping

_____________________

2. The Sierra Club and Ecology Center tested bags of commercial garden fertilizers for PFAS “forever chemicals” and found toxic levels in 8/9 bags

https://www.sierraclub.org/sludge-garden-toxic-pfas-home-fertilizers-made-sewage-sludge

-

Executive Summary

Sierra Club and Ecology Center tested home fertilizers made out of sewage waste for toxic PFAS chemicals, and we found the chemicals in every product, and at levels that exceed a screening standard set for land application in the state of Maine, the state with the strictest safeguards for PFAS contamination of agricultural lands. -

Introduction

About half of the sewage waste generated in the United States is treated and then spread on land, including agricultural crops and dairy land for disposal. The treatment doesn’t break down persistent chemicals like PFAS, which pose a threat to food crops and waterways. -

Recommendations

EPA, states, the chemical industry, and wastewater treatment plants must all act with urgency to keep PFAS out of the sewer system. Fertilizer companies should clearly label products as made from sludge so gardeners can avoid using them on home crops. -

The Fate of PFAS in Wastewater Systems, Agricultural systems, and the Food Supply Challenges of Biosolids Disposal

Our tests measured PFAS, precursor chemicals as well as unknown synthetic fluorine-based chemicals in much higher amounts than PFAS themselves. -

The Fate of PFAS in Wastewater Systems, Agricultural Systems, and Food Supply

PFAS are legally washed down sewer drains from homes and industry. EPA and states can limit pollution from industry, but the only way to end PFAS from homes and commercial businesses is to stop using the chemicals in consumer and industrial products. -

Challenges of Biosolids Disposal

Persistent chemicals like PFAS are not broken down during sewage treatment, and also create problems when burned in sludge incinerators. Even lined landfills eventually leak and release PFAS and other persistent chemicals back into the environment. -

References

-

Appendices

-

Acknowledgements

Executive Summary

Many home gardeners buy compost or commercial soil amendments to enhance soil nutrition. But new tests reveal concerning levels of toxic chemicals known as PFAS in fertilizer products which are commonly made from sewage sludge. These “forever chemicals” were found in all of the nine products tested by the Ecology Center of Michigan and Sierra Club and marketed as “eco” or “natural” and eight of the nine exceeded screening levels set by the state of Maine. PFAS in fertilizers could cause garden crops to be a source of exposure for home gardeners.

PFAS are per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances, a class of widely used industrial chemicals, that persist for decades in the environment, many of which are toxic to people. In most places, industries are currently allowed to flush PFAS-containing waste into wastewater drains that flow to treatment plants. The chemicals are not removed during sewage treatment and instead settle in solid materials that are separated out from liquids in the treatment process.

Americans generate massive quantities of sewage waste each day. Nearly half of sewage sludges are treated to kill pathogens and then spread on farms, pastures, and wildlands for disposal, where nutrients like nitrogen improve soil productivity. The wastewater industry and EPA call these “biosolids.” Unfortunately, biosolids carry a variety of persistent and toxic chemicals, in addition to PFAS, which can threaten our food supply and contaminate water sources.

The Sierra Club and the Ecology Center identified dozens of home fertilizers made from biosolids. We purchased nine fertilizers:

-

Cured Bloom (Washington DC)

-

TAGRO Mix (Tacoma, Washington)

-

Milorganite 6-4-0 (Milwaukee, Wisconsin)

-

Pro Care Natural Fertilizer (Madison, Georgia)

-

EcoScraps Slow-Release Fertilizer (Las Vegas, Nevada)

-

Menards Premium Natural Fertilizer (Eau Claire, Wisconsin)

-

GreenEdge Slow Release Fertilizer (Jacksonville, Florida)

-

Earthlife Natural Fertilizer (North Andover, Massachusetts)

-

Synagro Granulite Fertilizer Pellets (Sacramento area, California)

Our tests reveal that American gardeners can unwittingly bring PFAS contaminants home when they buy fertilizer that is made from sludge-biosolids. Eight of the nine products exceeded screening limits for two chemicals—PFOS or PFOA—set by Maine, the state with the most robust action on PFAS in biosolids. The chemicals were measured at levels that would not be acceptable for the state’s agricultural soils. Of the 33 PFAS compounds analyzed in the products, 24 were detected in at least one product. Each product contained from 14 to 20 detectable PFAS compounds. Additional tests showed they also contained two to eight times greater mass of precursor compounds and hundreds to thousands of times more unidentifiable synthetic fluorine compounds.

Our testing provides a snapshot of PFAS levels in complex wastewater systems. The findings are in line with national surveys of PFAS in sludge-biosolids, and academic studies testing biosolids-based fertilizers and composts. Available evidence suggests that PFAS and related chemicals in sewage sludge could jeopardize the safety of the commercial food supply and home gardens. We recommend home gardeners do not purchase biosolids-derived fertilizers for use on fruit and vegetable beds. For the large-scale problem of disposing of sewage waste, however, simple solutions are elusive. The federal government and most states have done little to study the issue, let alone address it.

Our test results suggest that urgent changes are needed to halt the unnecessary uses of PFAS in commerce and minimize the amounts that are discharged into our wastewater system. EPA Administrator Michael Regan has pledged immediate action to reduce the threats posed by PFAS uses, but the agency’s anemic responses to date, as well as structural barriers created by key environmental laws, make quick action unlikely and hinder even the most common-sense measures to contain the chemical crisis.

The EPA and states must take immediate action to keep PFAS and other persistent chemicals out of the wastewater system, biosolids, and the food supply. This means preventing industrial polluters from discharging PFAS in their wastewater drains. Agencies must survey the hazard of food production on highly contaminated soils and regulate land application of biosolids with high levels of PFAS and other chemicals. Industry must pay for the damages that PFAS production and use poses to people and the environment, including costly cleanups of contaminated places. The most efficient and effective way to protect people from the growing threat of PFAS exposure is to end the use of PFAS, with limited exemptions.

Introduction (excerpts)

· Treated sewage sludge or “biosolids” are commonly applied to farmlands and sold directly to home gardeners as compost, soil amendment or fertilizer. We identified at least 30 different commercial fertilizers made from sewage sludge and sold at retailers like Lowe’s, The Home Depot, Ace Hardware and Menards or direct from manufacturing or wholesale sites. Many bear terms like “eco,” “natural,” or “organic” on the label. While biosolids are not allowed to be applied on farms growing certified organic fruits, vegetables or dairy products (USFDA 2013), one of the biosolids-based fertilizer we tested is used in school gardens in Washington, D.C.

· EPA regulates pathogens and heavy metals like lead, cadmium and mercury in biosolids, but does not set limits for other chemical contaminants that accumulate in sewage and wastewater, including PFAS (per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances), which are a diverse group of synthetic (meaning human-made) fluorochemicals used widely for their useful qualities of thermal and chemical resistance and persistence. PFAS are generally not well regulated under national air, water, chemicals or waste laws, but widely understood to pose a serious health risk to people, wildlife and the environment (Kwiatkowski 2020, Fenton 2020).

· Treated sewage sludge, or “biosolids,” are commonly applied to farmlands and sold directly to home gardeners as compost, soil amendment, or fertilizer. We identified at least 30 different commercial fertilizers made from sewage sludge and sold at retailers like Lowe’s, The Home Depot, Ace Hardware, and Menards, and direct from manufacturing or wholesale sites. Many bear terms like “eco,” “natural,” or “organic” on the label.

· We tested a sample of nine products marketed to home gardeners for PFAS. Most products contained 100 percent sludge-biosolids. But none bear any warnings about the potential inclusion of PFAS or most other chemical contaminants. Just one had a warning about molybdenum for forage crops.

· Shoppers can check the “Guaranteed Analysis” section of the product label that discloses the source of the fertilizer. If purchasing compost or topsoil, check product information for terms like “biosolids,” “residuals,” or “municipal waste,” which could indicate it is made from sewage.

· But quick fixes are more elusive for the threat sludge-based biosolids pose to the commercial food supply. The EPA requires biosolids be tested for phosphorus, pathogens, and nine heavy metals before land application in its Rule 503, but does not set any limits for any PFAS compounds (USEPA 1994). The EPA provides an annual update about the number of unregulated chemicals that have been detected in the materials (USEPA 2021a). In a 2018 report, the EPA’s Inspector General raised concerns about gaps in its oversight of biosolids materials (USEPA 2018). It cautioned that the agency should consider the cumulative hazards posed by other persistent contaminants in biosolids and revise its public messages about biosolids safety (USEPA 2018).

· Despite being highly persistent, bioaccumulative, mobile, and toxic to people, PFAS chemicals are virtually unregulated. Three PFAS chemicals—PFOS, PFOA and PFHxS—are in the process of being phased out of commerce under the global United Nations Stockholm Convention, but thousands more are commonly used in a variety of consumer and industrial products.

· The EPA stalled listing these clearly harmful chemicals under the nation’s clean air and water and waste laws, and continued to approve new, poorly studied PFAS chemicals as alternatives to PFOS and PFOA. In the meantime, industries like metal plating, paper, and textile manufacturing continue to legally dump the chemicals into wastewater drains.

· The Clean Water Act allows the EPA to set contaminant limits for biosolids, and the agency has pledged to do a safety screening for the hundreds of unregulated contaminants detected in biosolids in the next two years (USEPA 2019).

· After discovering high levels of PFAS in milk produced from dairy cattle feeding on contaminated fields, Maine is measuring the amount of PFAS in biosolids and ensuring that the materials do not contaminate agricultural lands (Maine 2021). When biosolids exceed screening levels, the state requires modeling or testing to ensure the repeat application has not pushed agricultural fields over the screening level of 2.5 ppb for PFOA and 5.2 ppb for PFOS. Maine’s testing of one contaminated dairy found that the PFOS and PFOA levels in milk exceeded the concentrations it measured in the soils themselves.

_____________________

3. Tabuchi, H. (2024, August 31). Something’s Poisoning America’s Land. Farmers Fear ‘Forever’ Chemicals. Fertilizer made from city sewage has been spread on millions of acres of farmland for decades. Scientists say it can contain high levels of the toxic substance. New York Times. Link.

Tabuchi, H. (2024, August 31). 5 Takeaways From Our Reporting on Toxic Sludge Fertilizer. New York Times. Link.

Tabuchi, H. (2024, September 21). Her Children Were Sick. Was It ‘Forever Chemicals’ on the Family Farm? Pastures were fertilized with toxic sewage sludge decades ago. Nobody knew, until the cows’ milk was tested. New York Times. Link.

Tabuchi, H. (2024, December 6). Their Fertilizer Poisons Farmland. Now, They Want Protection From Lawsuits: A company controlled by Goldman Sachs is helping to lead a lobbying effort by makers of fertilizer linked to “forever chemicals.” New York Times. Link.

Tabuchi, H. (2024, December 27). The E.P.A. Promotes Toxic Fertilizer. 3M Told It of Risks Years Ago. New York Times. Link.

Tabuchi, H. (2025, January 14). In a First, the E.P.A. Warns of ‘Forever Chemicals’ in Sludge Fertilizer. New York Times. Link.

Tabuchi, H. (2025, January 14). What to Know About ‘Forever Chemicals’ in Sludge Fertilizer. New York Times. Link

Tabuchi, H. (2025, February 14). Texas County Declares an Emergency Over Toxic Fertilizer. New York Times. Link.

Tabuchi, H. (2024, March 30). A maker of sewage-based fertilizer leaves town amid a toxic crisis. The New York Times. Link.