NYT piles on the lies about measles

Just reviewing this story published on March 6 by a Times fellow (a new reporter) designed to scare the **** out of parents

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/03/06/health/measles-death-new-mexico.html

The measles virus, which spreads when an infected person breathes, coughs or sneezes, is extremely contagious. Each infected person can spread the pathogen to as many as 18 others.

Where did the number eighteen come from? Maybe you can spread it to a whole indoor stadium? There is no way to know this number accurately, as it is based on the theoretical construct (R sub zero) of how many you might infect if no one had any immunity at all to measles.

Within a week or two of being exposed, those who are infected may develop a high fever, cough, runny nose and red, watery eyes. Within a few days, a telltale rash breaks out, first as flat, red spots on the face and then spreading down the neck and torso to the rest of the body.

In most cases, these symptoms resolve in a few weeks.

It does not take “a few weeks” to resolve. Most kids are back in school in a week or less as I recall.

But in rare cases, the virus causes pneumonia, making it difficult for patients, especially children, to get oxygen into their lungs.

The infection can also lead to brain swelling, which can cause lasting damage, including blindness, deafness and intellectual disabilities.

For every 1,000 children who get measles, one or two will die, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

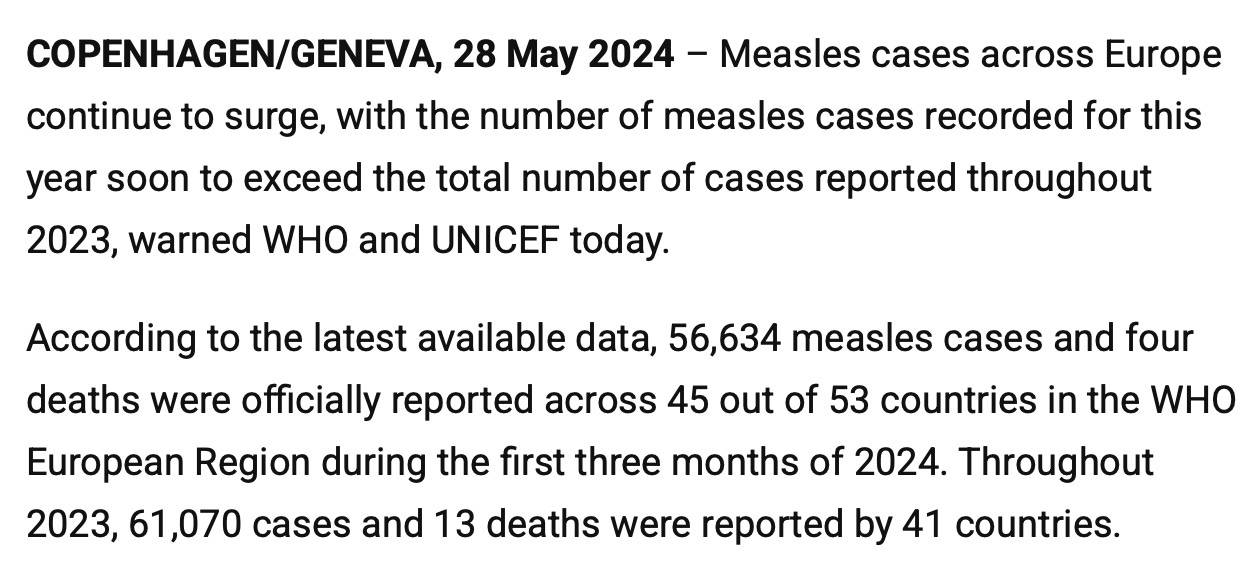

Oh really? Let’s look at some real numbers. What does UNICEF have to say about this? Europe has lots of cases, and eastern Europe is much poorer than the US. How many kids die there?

So for the first quarter of 2024, 1 child died per 14,000 measles cases. In 2023, one child died for every 4700 reported measles cases. But death rates were likely lower, as not all cases get reported.

The virus also weakens the immune system in the long term, making its host more susceptible to future infections.

This theory is based on 2 studies that found fewer B cells and 20% fewer antibodies and a lower range of antibodies after a measles infection.

These 2 studies got a huge amount of attention, occurring as they did right after a major measles epidemic in the US. However, neither study actually looked to see if kids were more likely to catch infections as a result of this shift in antibodies. You would think that would be the first things scientists would look for, but in the real world the first thing they seek is something publishable. Hey, if you actually looked for infections, it might prove your beautiful theory wrong, and then you would have wasted more time, only to lose your hot publication. Nor did they look to see for how long this putative erasure of immunological memory lasted. No, it was all about the headline. And the subheading: get your vaccination.

Measles vaccine gives you a very mild case of measles. Africa is where children are the most stressed by exposure to infectious diseases. Dr. Christine Stabell Benn has been studying children after they get a measles vaccine, compared to those who don’t get one, and believes they have a strengthened immune system. Hmmm. Vaccination introduces a weakened strain of measles into your body. Why would it strengthen immunity if a regular case of measles makes you lose immunity? It simply does not make sense.

A 2015 study found that before the M.M.R. vaccine was widely available, measles might have been responsible for up to half of all infectious disease deaths in children.

Might have been. Yup. If there was no HIV, no TB, no diarrhea and no pneumonia, it might have been. What a great way to end the article. Speculation disguised as fact. I think this junior reporter needs to go back to journalism school. Or is this how they teach you to do journalism nowadays?

Teddy Rosenbluth is a health reporter and a member of the 2024-25 Times Fellowship class, a program for journalists early in their careers. More about Teddy Rosenbluth