The WHO takes up climate change; Lawrence O. Gostin spins the Pandemic Treaty; and RFK, Jr. takes a chainsaw to the WHO with Javier Milei

An exciting day

- The WHO reported the following today, exaggerating progress on its climate change plan, as noted in the final sentence. Remember how I told you the globalists were trying to equate health with stopping climate change?

Assembly adopts the Global action plan on climate change and health for 2025–2028

At the Seventy-eighth World Health Assembly in 2025, Member States expressed support for the first-ever draft Global action plan on climate change and health, marking an important step forward in global health and climate policy. The draft Global action plan 2025–2028 (EB156(40)) acknowledged the urgent need to address the health impacts of climate change, positioning health systems as part of the climate solution.

It aims to provide a strategic framework to guide Member States, the WHO Secretariat and other stakeholders in developing climate-resilient, low-carbon health systems; enhancing surveillance and early warning systems; protecting vulnerable populations; and integrating health into climate policy and financing mechanisms.

Building on commitments made at previous Conference of the Parties (COPs) and the outcomes of the Executive Board meeting in February 2025, this plan supports WHO’s work to promote health leadership in the global climate agenda and coordinate country-level action and implementation. By supporting this Global action plan, the Assembly affirmed that climate action is not only an environmental priority but also a strategic health priority.

While recognizing this important progress, some Member States noted that more time and dialogue are needed to reach consensus on certain principles and language used in the action plan moving forward.

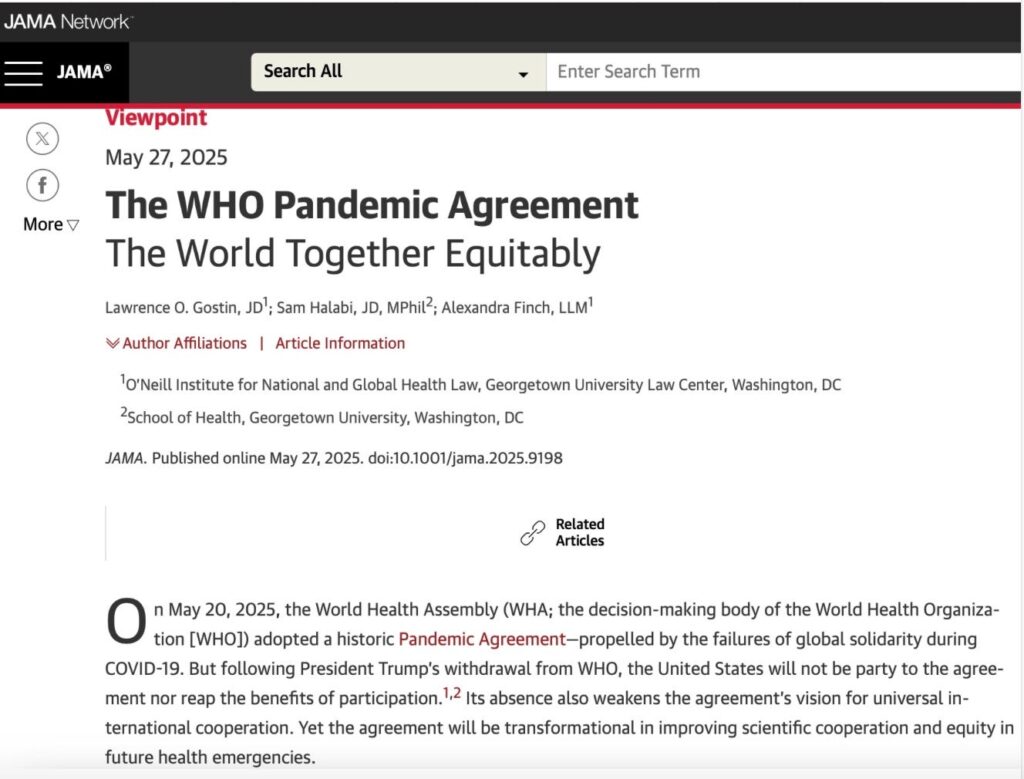

- Our friend the ubiquitous (or was it iniquitous?) Lawrence O. Gostin, professor of global health law at Georgetown University, director of a WHO Coordinating Center and major pooh bah for globalism, published a piece in the JAMA today about the Pandemic Treaty, making it out to be quite different than what the actual words say. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2834765

Read it and barf, because there is so much “equity” and misrepresentation slathered into his opinion piece. As it is paywalled I will include the rest below the screenshot.

Pandemic Prevention, Preparedness, and Response (PPPR)

The agreement lays out a comprehensive framework for action on pandemics, including preventing zoonotic spillovers, health system preparedness, and equitable pandemic response.

Pandemic Prevention Through “One Health”

The agreement is the first to codify a One Health approach, which recognizes the interconnectedness of human health, the health of domesticated and wild animals, and the environment.3 Most emerging diseases are zoonotic—involving pathogens that spill over from animals to humans. The agreement therefore requires countries to develop national pandemic prevention and surveillance plans including measures to identify and mitigate the drivers of disease at the human-animal-environment interface, prevent spillover, and implement robust surveillance and risk assessment of pathogens (Article 4). [Note: they are told to plan, but not to carry out any actions—Nass]

Parties are encouraged to consider the factors that increase pandemic risks (eg, deforestation, land use, and climate change) in their national policies4 and to establish joint training for workforce at the human-animal-environment interface (Article 5). These obligations are designed to minimize the risks of pandemics by preventing them at their source.

Health System Capacities

In the event a pandemic does emerge, the agreement builds on the International Health Regulations (IHR) by strengthening health system capacities with a focus on primary care and universal health coverage. These include equitable access to scalable clinical care and routine essential health services, as well as strengthening laboratory and diagnostic capacities. Health workers on the front line would gain priority access to pandemic response products during emergencies and would at all times have decent work and protection from violence and harassment (Article 7). [How? that is only an aspiration, not a program—Gostin loves conflating the two—Nass]

Equitable Access to Medical Products

The COVID-19 pandemic was characterized by inequitable distribution of diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccines—spurred by prepurchasing and hoarding of lifesaving products by high-income countries and the collapse of supply chains. The agreement would transform the current development and distribution model from one reliant on charitable donations to an end-to-end ecosystem infused with equity. {Aspirational only—Nass]

Article 8 requires states to strengthen regulatory agencies to align with international standards for quality, safety, and efficacy of countermeasures. [No, they are only asked to “take steps” and are not required to align with first world standards—Nass] Article 9 would strengthen research and development capacities, investments, and partnerships and require states to share products for use as comparators in clinical trials, as well as posttrial access for trial participants. The agreement asks governments to build equitable access into their publicly funded research and development agreements—a policy to help ensure that public funding results in public benefit.

The agreement’s commitments for sustainable and geographically distributed pharmaceutical manufacturing are transformational. Currently, most pandemic products are manufactured in a small number of high-income countries. Article 10 seeks to build up product development and manufacturing in multiple regions, which could be scaled during an emergency. [There is no money or plan for getting this done, and so far it has not worked when tried—Nass]

Pharmaceutical companies in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) often require transfer of technology and know-how from technology holders in high-income countries to expand and accelerate production. Article 11 therefore calls on states to facilitate technology transfer, including to established technology transfer hubs like WHO’s Health Technology Access Program, and to offer licenses to government-owned technologies. Negotiations were contentious: high-income countries pushed for technology transfer to be entirely “voluntary,” which LMICs strongly rejected. The final text facilitates transfer of technology on “mutually agreed” terms—preserving LMICs’ use of flexibilities under the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS Agreement), which allows countries to grant compulsory licenses where voluntary negotiations fail. [Maybe—this too was very controversial—Nass]

Negotiations over a pathogen access and benefits sharing (PABS) system were equally combative. PABS represents a “global social bargain”5: pathogen samples and genomic sequencing data would be shared with a central repository that participating manufacturers could access to develop medical countermeasures and in exchange would aim to [this was left vague due to inability to agree on it—Nass] provide 20% of their real-time production (at least 10% as a donation and the rest at affordable prices) to WHO to distribute based on public health need. For the modalities of the PABS system, the WHA charges an Intergovernmental Working Group to negotiate a PABS Annex to the treaty. Crucially, the whole agreement cannot open for signature by countries until the annex is adopted—tying the agreement’s fate to successful negotiations of a PABS Annex. [At least he got that right—Nass]

Supply Chains

During the pandemic, all countries experienced supply chain disruptions of products and raw materials. The agreement therefore establishes a WHO-led global supply chain and logistics network (Article 13), while imposing new state obligations on procurement and distribution, including avoiding stockpiling and export restrictions (Article 14), which created supply shortages. [No, the supply chain is aspirational, too, left to the Conference of Parties to work out later. The COP can only make non-binding recommendations, so it will be a miracle if this actually happens—Nass]

Health Information and Literacy

During the pandemic, the proliferation of false and misleading health information impeded an effective response. To build public trust and strengthen health literacy, Article 16 encourages states to be transparent and accurate when sharing information. Monitoring and correcting false information on social media is contentious given the value of freedom of expression.

Financing

Sustainable financing for PPPR is essential. LMICs pushed hard to establish a robust financing mechanism, but negotiators could not agree on a special fund, and the agreement did not require state financial contributions. Negotiators did agree on a Coordinating Financial Mechanism (Article 18) to jointly support the agreement and the IHR, charged with conducting a financial needs and gaps assessment, operating a dashboard of available resources, and leveraging voluntary contributions.

Governance

Like international agreements covering tobacco control, biodiversity, and climate change, the Pandemic Agreement will be governed by a Conference of the Parties (COP). The COP is charged with reviewing the agreement’s functioning, is empowered to make recommendations, and can develop annexes and protocols—for example, detailing One Health obligations. [Sorry, Larry, the COP cannot obligate nations, although I am sure that in earlier drafts that you helped write, there were plenty of obligations imposed. They were removed—Nass]. Many observers decry international law because legally binding instruments often lack enforcement mechanisms, and the Pandemic Agreement is no exception. Instead, the agreement establishes an implementation mechanism that, like the IHR’s States Parties Committee, is expressly nonadversarial and essentially toothless (Article 19).

A Global Agreement Without the United States

Before its withdrawal from WHO, the United States regularly played the role of bridge-maker, finding common ground between delegations. But the United States (like many European countries) also opposed robust technology transfer and PABS and was protective of the intellectual property of its pharmaceutical industry.

Despite the departure of the United States, or maybe even because of it, the agreement was adopted and will operate entirely without the United States. While there is still scope for US universities, researchers, and pharmaceutical companies to engage in agreement mechanisms, the United States will be on the outside looking in on issues crucial to its national interests, such as PABS-facilitated scientific exchange. Its absence represents a lost opportunity for the United States and the world. Universities and businesses in other countries, primarily Europe, South America, and Asia, will benefit from investments and incentives spurred by the agreement. Moreover, partnerships the agreement facilitates could proliferate technology transfer arrangements to the exclusion of the United States, marginalizing the country when future health emergencies arise.

A great deal can and will be accomplished by the Pandemic Agreement without the United States. But the United States is irreplaceable. The sheer power of its financing and influence will be missing. Perhaps more important is the power of US science. Through scientific expertise in federal agencies, cutting-edge academic research, and the discoveries of pharmaceutical companies, the absence of the United States creates a gaping hole in pandemic preparedness.

To be sure, the Pandemic Agreement lacks ambition in parts, is couched in hortatory language, and has no enforcement mechanism. Yet its adoption is a major landmark in global health security and a triumph for multilateralism in a highly fragmented world.

If you want to read the final version of the Treaty or my comments on the treaty, both can be found here.

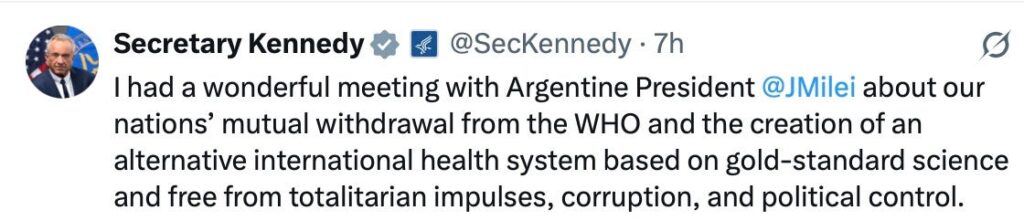

As best I can tell, the chainsaw is engraved with the words “Las Fuerzas del Cielo” meaning “The Forces of Heaven,” which is also the name of a group aligned with Milei in Argentina. So be it.