Farmers Can’t Make Money–the deck is stacked against them in so many ways. Some charts and graphs show the dire condition of farming in the US

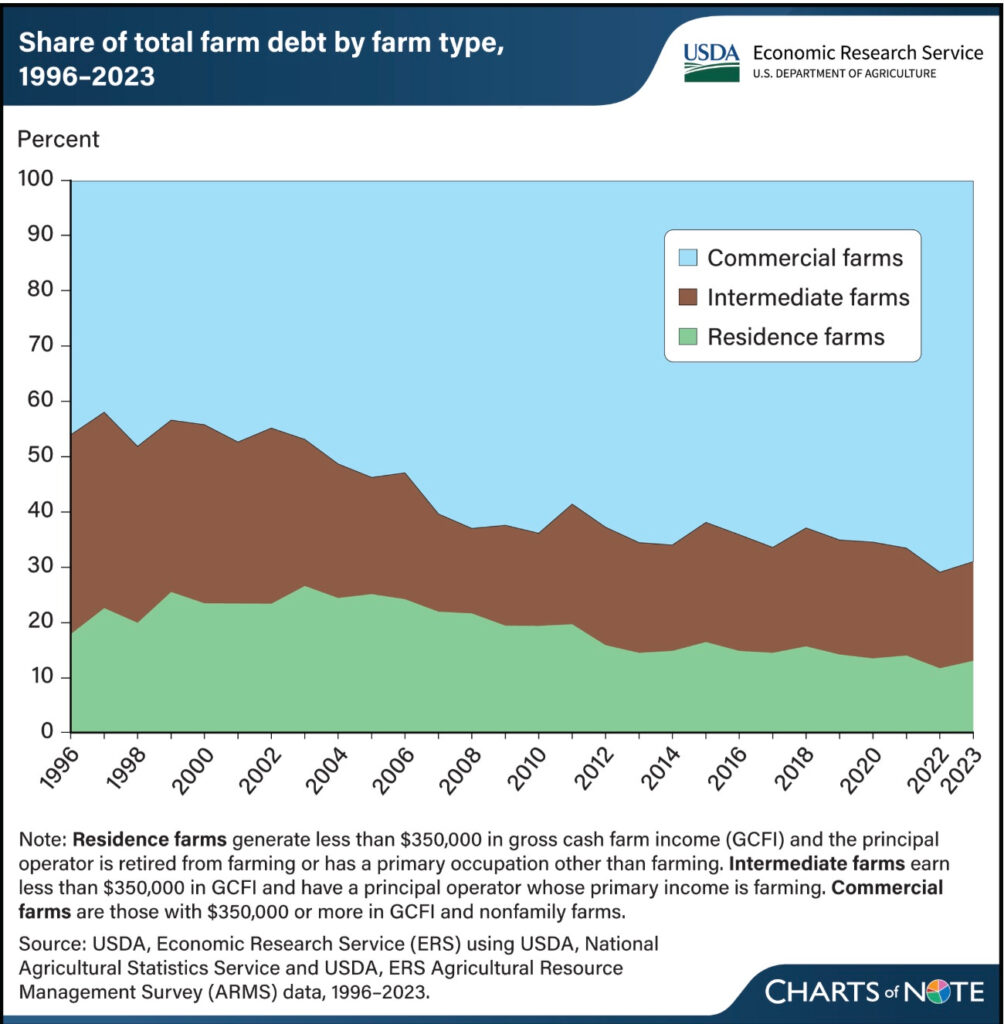

Even the big guys are more in debt, though that could reflect their landgrabbing

https://ers.usda.gov/data-products/charts-of-note/chart-detail?chartId=112608

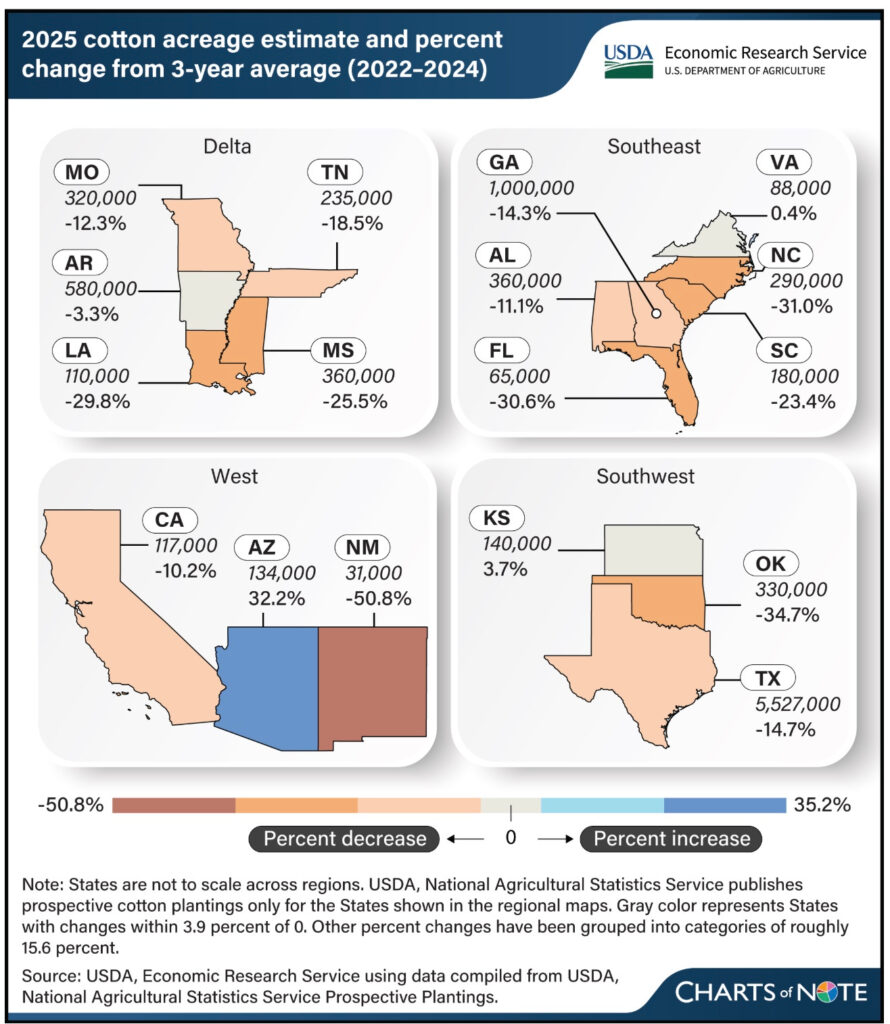

Considerably less cotton is being planted in prime cotton locations. Fourteen states are planting les acreage in cotton, while 3 states have increased their acreage, but Virginia by only 0.4% and Kansas by only 3.7%

Commercial farms have increased their %age of total farm debt from 42% in 1996 to 69% in 2023—an increase of 64%. Of course, some of this debt is probably due to borrowing to buy up small farms that have gone out of business.

https://ers.usda.gov/data-products/charts-of-note/chart-detail?chartId=112679

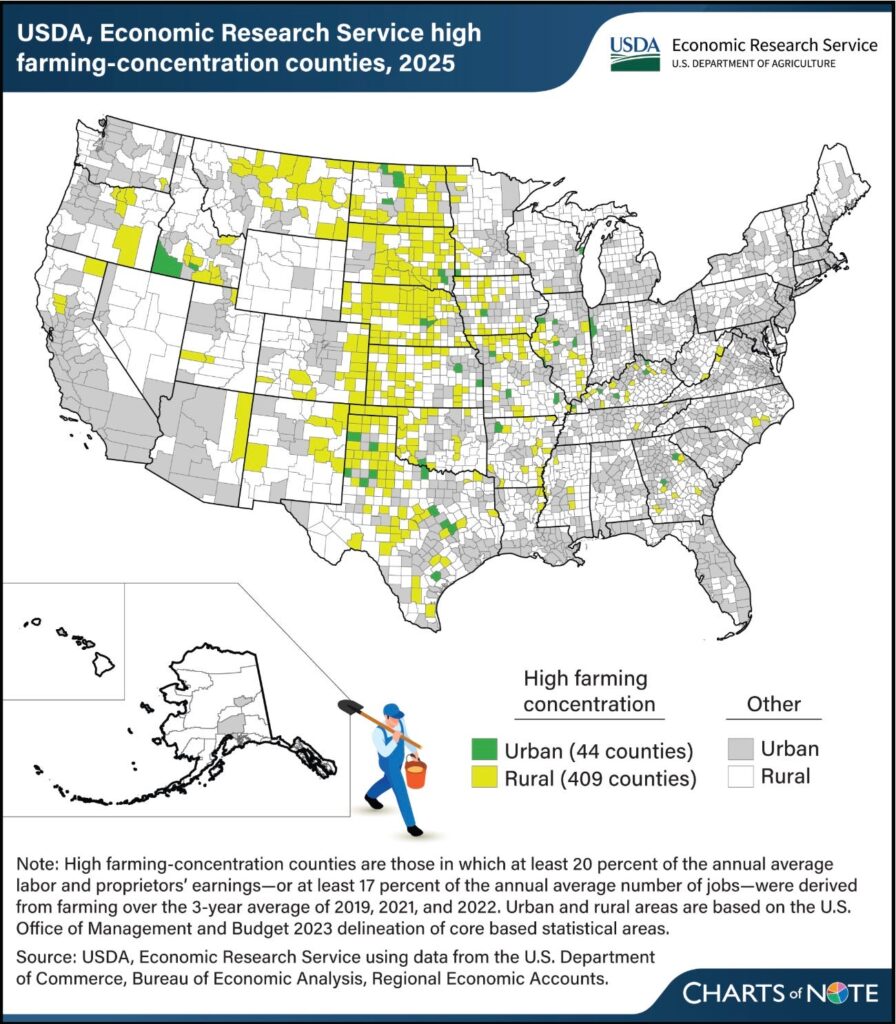

The major farming areas are in flyover zones, far from the seats of power in the US, and small farmers’ opportunities to affect government policies are extremely limited.

https://ers.usda.gov/data-products/charts-of-note/chart-detail?chartId=112606

Corngrowers seem to lose money every other year. It is obvious why they are desperate for the massive ethanol (“gasahol”) subsidies they receive, even though it is a massive waste of money for taxpayers, who subsidize a completely uneconomic industry. According to Pennsylvania State U:

Problems with Ethanol

Many people have noticed problems when using ethanol-blended gasoline. The more common issues attributed to ethanol include the following:

Fuel Energy

Ethanol contains about 30 percent less energy per unit volume than gasoline. As a result, a 10 percent ethanol-gasoline blend will have 97 percent as much energy as gasoline. In reality, that’s not a very big difference. If you notice a difference in performance when running on E10, it is likely due to other factors, such as those that follow.

Fuel Contaminants

Gasoline is not water soluble, but ethanol is. Therefore, ethanol can pick up contaminants that gasoline doesn’t and may deposit those contaminants inside your engine, leading to fouled filters or injectors. This can cause noticeable decreases in engine performance if not dealt with. Engines that are rarely or seasonally used, such as lawnmowers or chainsaws, are especially prone to difficulties, although the reasons are not all clearly understood. Proper formulation and care of ethanol blends is something that fuel transporters and resellers are getting the hang of, so hopefully this will be less of a problem in the future.

Seals and Hoses

On old machinery, seals and hoses on engines and fuel systems tend to be weak and susceptible to degradation. Ethanol in gasoline can cause them to deteriorate, shrink, or swell, resulting in leaks.

Fuel-Air Ratio

Ethanol molecules include oxygen atoms, whereas gasoline molecules don’t. That’s part of the reason why ethanol has less energy than gasoline. Another effect of the oxygen from ethanol is that ethanol blends tend to run “leaner” than pure gasoline because there is more oxygen available in the fuel-air mixture. If your engine is not able to compensate by reducing the incoming airflow, the resulting combustion conditions in the engine cylinder may be less than ideal. Newer vehicles are generally designed to take care of this automatically, but older engines may need a bit of manual adjustment to get the air-fuel mixture just right.

Some people have reported engines overheating when ethanol blends are used, suggesting that ethanol burns “hotter.” This is a bit mysterious since ethanol contains less energy per unit volume than gasoline, and the flame temperature of ethanol is more than 40°C cooler than gasoline. The most likely explanation is related to the air/fuel ratio. Most engines are designed to run with an excess of fuel relative to the amount of air (a “rich” mixture); experience has shown that this leads to higher power output and cooler engine temperatures. When ethanol blends are used, newer engines are equipped with sensors to adjust the air/fuel ratio automatically. Older vehicles and small engines may not be equipped to do this, resulting in a “leaner” burn that may increase engine temperatures and/or reduce engine power. A simple adjustment to the fuel system to “richen” the mixture can often fix this problem.

And

The ethanol industry uses about 40 percent of America’s corn crop. That’s a lot, even when you take into account that a great deal of the corn for ethanol becomes “distiller’s dried grains,” a high-protein animal feed.

However, Penn State points out that adding ethanol to gasoline replaced the use of toxic MTBE, a very good thing. But it also looks like growing corn is a guaranteed way for farmers to stay on the knife edge of financial viability. In half the 18 years from 2005-2022, they lost money on corn. In 2023 they barely broke even.

It seems to me this needs a fix.

https://ers.usda.gov/data-products/charts-of-note?cpid=email&page=2

Farmworkers are poorly paid. The following USG data come from May 2023:

https://www.bls.gov/oes/2023/may/oes452092.htm

The inspections and standards for imported organic foods are questionable. Imported “organics” are pricing out America’s organic farmers, who must meet higher standards that producers who export to the US. However, even US organic certifications are problematic, and the system begs for improvement.

https://ers.usda.gov/data-products/charts-of-note/chart-detail?chartId=111163

Food security —and especially the percentage of food insecure households in the US— is measured by census takers asking questions of 30,000 families, and extrapolating the results to the US population.

A description of the method can be found here:

However, the USDA sponsored the analysis, so of course it says the method is a good one. But is it? The article suggests other methods could be used as well, and the results compared, which to me makes a lot of sense.

I don’t think the basis for the $113 Billion spent annually on food stamps (SNAP) is solid. Nor do the article’s authors:

SNAP

SNAP is the nation’s largest antihunger program and a key part of the social safety net, providing food spending support to 40 million people monthly in 2020. A large literature finds that SNAP improves household food security.52,77e82 Evaluation efforts are challenging, because people who participate in these programs may differ systematically from those who do not. Cross-sectional comparison shows that SNAP participants have high levels of food insecurity. Among households with income below 130% of the federal poverty level (a gross income threshold used in SNAP eligibility determination), 45.4% of SNAP participants in 2020 were food insecure and 24.8% of SNAP nonparticipants were food insecure.2 Results from studies that sought to control for this selfselection have varied depending on the methods used. Older studies using simultaneous equation models,83 fixed effects models,84 and propensity score matching85 have found unclear evidence regarding the relationship between SNAP and food security, often reporting positive but not statistically significant estimates. These older studies shed light on the nature of confounding factors suggesting that unobserved factors are probably time-varying and affect from time to time. More recent studies have found that SNAP participation reduces the severity or incidence of household food security. These studies use instrumental variables approaches,78,81 fixed effects,86 and partial identification bounding methods,87 regression discontinuity design,88 among others. A study by Gregory, Rabbitt, and Ribar89 replicates the modeling strategies used in the literature and finds that SNAP reduces food insecurity, but effects might differ across subpopulations and are not always statistically significant.

It does not make sense that large numbers of needy people are allegedly not receiving SNAP benefits, when 40 million Americans do receive them. When a single person can receive up to $297/month in food stamps, depending on income, it seems they should no longer be food insecure. If 12% of Americans remain truly food insecure for some part of the year (which is how the survey defines food insecurity) despite about 12% of the population receiving food stamp benefits, are the benefits reaching the right people? Is asking people whether they are food insecure a reliable method for assessing how many Americans are actually short of food? Are they purchasing nutritious foods? Ten per cent of SNAP benefits has been spent on soda.

In 2023, average SNAP benefits were $212 per person per month and the program cost $113 Billion overall, or about $2800 pppy averaged out.

What would it take for corn farmers to grow cows instead?