Which arbitrary path should be followed for ostriches that tested positive for avian flu: the one for wild birds, for domestic poultry or for cows?

1) Ignore; 2) Cull the entire flock; 3) Remove the affected animals temporarily and wait till the infection is over; 4) Meryl's plan?

There is a herd of 450 ostriches in British Columbia, Canada and two of the birds tested positive for bird flu on December 30. There were deaths in the flock.

The thing is, neither the ostriches nor their eggs were being used for food. The eggs were sold for scientific work on antibodies.

That did not stop the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) from issuing a cull order for the entire herd, with a deadline of February 1. (A group of ostriches can be called a flock or a herd—look it up if you don’t believe me—making the comparison to cows that much stronger. Maybe.)

But if they can cull ostriches for bird flu, they can cull mink and foxes—oh, yes, that was done in Finland in 2023. Can they cull cats and dogs?

The owners began a GoFundMe for legal costs and challenged the agency. Like elephants, and humans, ostriches have a lifespan of 75 years. Oh my, will they cull elephants? You can’t just replace a flock of ostriches like you can a flock of chickens, in a few months.

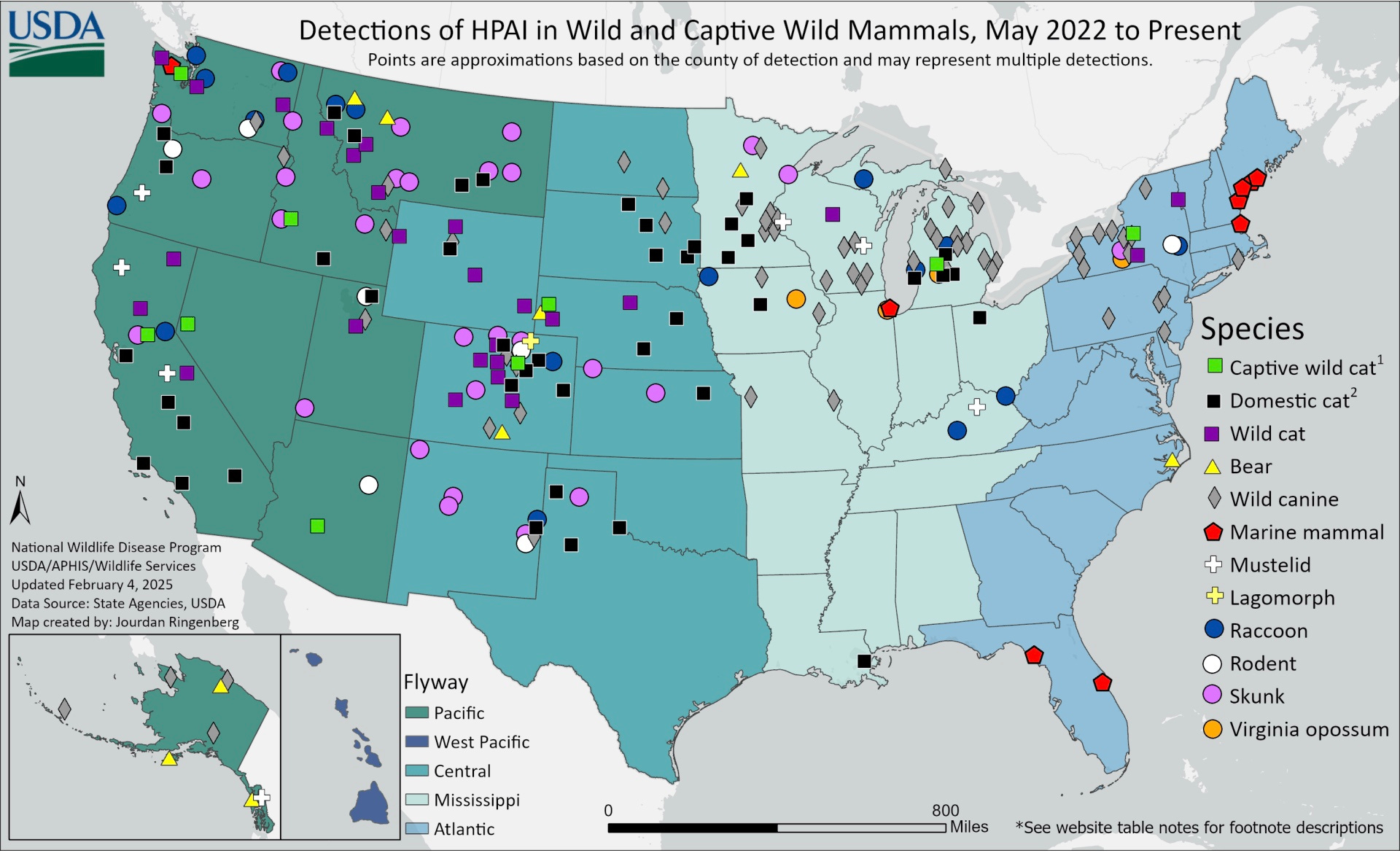

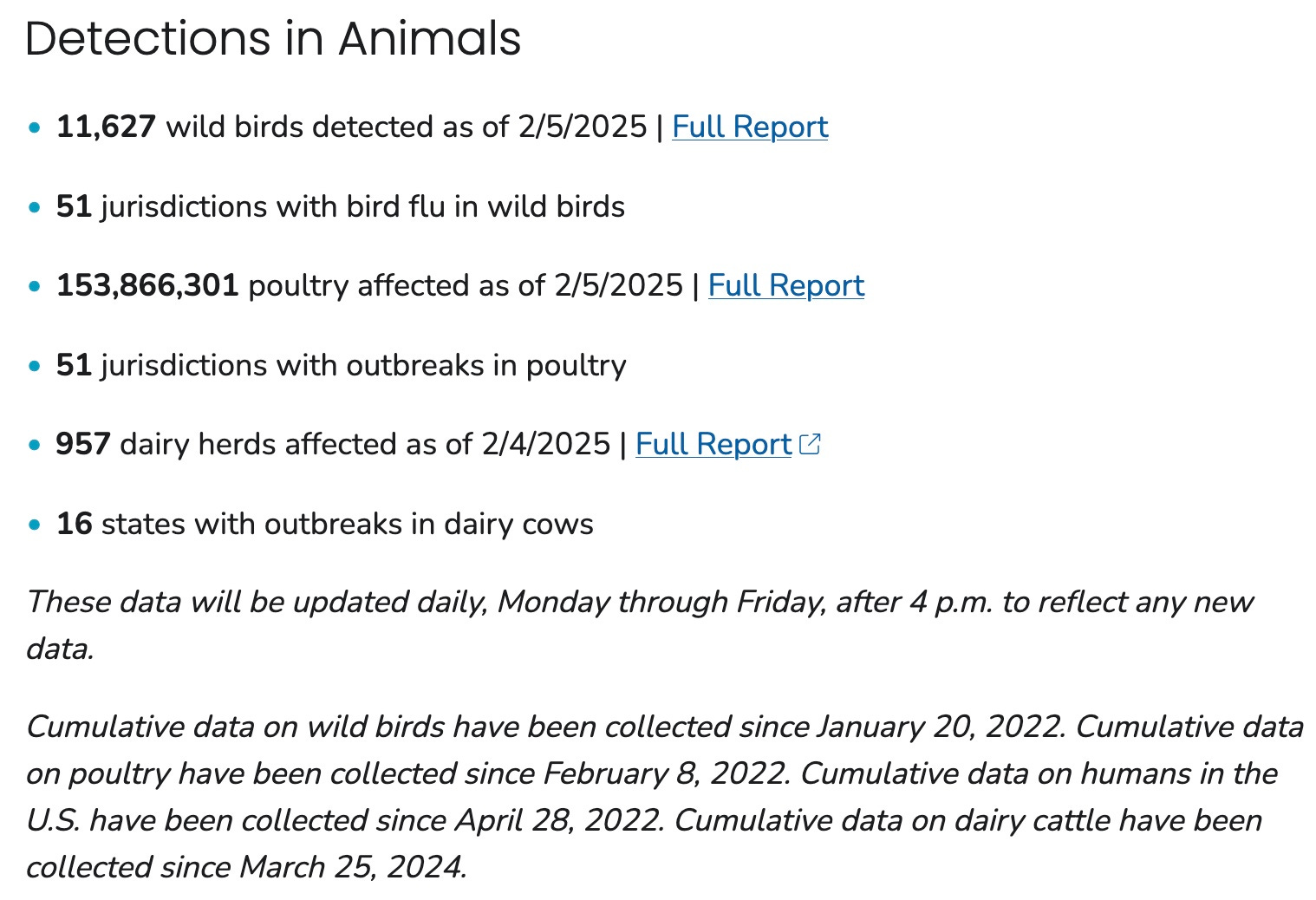

It seems you can find avian flu almost anywhere you look. Here is a USDA website listing the animals and locations in which H5N1 bird flu was identified in the US:

Well, at the last moment a judge stayed the cull order, pending a trial on the matter. While the owners believe that the deaths have ended and the flock is now immune from bird flu, by the time the case gets to court (in months or years) there will be no question as to whether the flock still harbors active bird flu infections. It won’t.

Did the Canadian government agency want to stave off the possibility of having live, immune birds whose antibodies and immune response could be studied, and which could, potentially, contribute to the development of non-vaccine therapies?

Why does a food agency have jurisdiction over non-food animals anyway?

“There is a risk of human transmission. There is a risk of illness and death,” Saunders said.

So what if the virus mutated? That is what it is doing in wild birds. All viruses mutate. This is not smallpox, and you cannot rid the planet of avian flu.

Instead you need to learn to live with it. Culling chickens is what has led to the majority of human cases—in the workers who do the culling. So if you want the virus to have access to more humans to mutate in, then keep up the culling!

What I suggest is to

- Get a 100% validation of the bird flu tests being used.

- Test what happens to a chicken house when you don’t cull, after a chicken tests positive. Remove all the chickens and eggs from the food chain. But continue to treat them as you would otherwise. How many die? How many recover? Can you detect viable virus in the flock? For how long? Feed raw and cooked chicken and egg to experimental animals and see if you can transmit the disease. Does any virus mutate so that it becomes more pathogenic to humans? Once these tests have been done we can use common sense to choose the right strategy and decide whether containment of any kind is necessary.

- Similar experiments should be done with cows.

- Stop all GOF research on bird flu (and everything else) immediately.

- Investigate why the highly pathogenic bird flu mutations were published: whose idea was that? Who gave the okay? Why is the US government paying for published research that tells the world how to create a deadly bird flu?